Her attention and focus improved immediately, and we enjoyed a remarkably easy Christmas holiday. When she returned to school, the positive reports came in almost immediately. Her speech language therapist reported that she'd had her best day ever — and had actually been chatting, that is, making conversation rather than using speech for purely pragmatic purposes.

Her teachers commented that she was starting to follow along in group discussions during class. And the formal assessment of the effectiveness of the medication — something called a SNAP-IV survey — showed remarkable gains in her behavior.

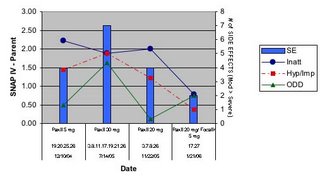

These two charts show the changes in her various symptoms when treated with Paxil alone, versus when treated with a combination of Paxil and Focalin. Although there is a slight increase of obsessive symptoms when the stimulant medication is added, the drop in inattentiveness and impulsivity is pronounced.

It's odd to think of a bar graph as a sort of picture of one's child, but in so many ways, it can be — each bar is a snapshot of her behavior (or, more accurately, my assessment of her behavior) at particular junctures.

And just in case my answers are skewed — impacted by my knowledge of her medications — there is also the classroom teacher's evaluation, which shows a similar effect, though with fewer "snapshots."

About six weeks after we started seeing these genuinely positive results from the Focalin, the FDA issued a black box warning —its most serious warming — on all ADHD stimulant medications, Focalin among them.

I heard the news on the radio and at first it seemed serious: 25 children who were taking one of these medications, had died suddenly with strokes or heart failure. Sweet M's godmother, who was visiting at the time, shared her concerns. I wondered and worried:

What did it really mean? What were parents supposed to do? What were we going to do?

It took a while to sort out the implications of this most recent panic, but the reality is that the FDA's decision to black box these medications was not based on any new evidence or new studies. Rather it was based on the fact that a total of 25 people, among the millions who are now prescribed stimulant medications, suffered from cardiovascular failure. It is not unusual for 25 individuals in a million to have such failures, even without medications.

Dr. Edward Hallowell, who specializes in the treatment of ADHD, writes in the Los Angeles Times:

The [FDA] recommendation was based on an upsurge in stimulant prescriptions, which the panel found alarming when coupled with 25 reports of sudden deaths in people taking the medications — even though there was no proof the stimulants caused the deaths. In other words, it isn't that the drugs are more dangerous than we thought, it's that they're probably being too freely prescribed: A federal survey found that nearly 1 in 10 12-year-old American boys takes a stimulant.So why the panic? Panic and risk management are an increasingly prevalent state of mind and response to contemporary events. Cultural critics Toby Miller and Marie Claire Leger have written a valuable article that makes the point that contemporary parents are engaged in a complex calculus of risk management. In a rapidly changing global order where there is the risk of occupational obsolescence not only for ourselves, but also for our children, parents are engaged in ongoing assessments of what is riskier for their children: taking a stimulant medication and remaining competitive in school, and subsequently, it is hoped, in a global economic context, or exposing their children to potential side effects from various psychotropic medications, Ritalin among them.

Stimulants have been used since 1937 to treat what we now call attention deficit disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Used properly, they have been proved safe and effective. Like all medications, and even water, stimulants used improperly can be dangerous, even fatal. But keep perspective: Aspirin is more dangerous for adults than stimulants. And penicillin is estimated to kill 500 to 1,000 people each year. Yet we rightly revere aspirin and penicillin, while cautioning that they be used with care. No black box needed.

So what about those 25 sudden deaths? First, it is not at all clear that because a person dies when taking a certain medication, the drug caused the death. Nor is there evidence that the number of sudden deaths is statistically significant — meaning more than random. There are 30 unexpected, sudden deaths per year per 1 million children between the ages of 10 and 14. More than 1 million children of that age take stimulants. Of the 25 deaths cited by the FDA panel, 19 were children. Therefore, we cannot conclude that stimulants raise the risk of sudden death.

Miller and Leger are building on the work of German social theorists Urlich Beck and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim, who argue that we are moving into a new period of modernity that has as its main features a highly atomized form of individuality that they call individualization. In this context, class affiliation and social status become less important. And instead of engaging in a battle for access to resources, we find we are engaged in all sorts of activities intended to minimize our risks. They call this "the risk society." In a sense, we all become unconscious insurance actuaries, trying to assess what course of action will offer our selves and our children the greatest chances to survive, and we might even hope — on a good day — thrive.

Miller and Leger are building on the work of German social theorists Urlich Beck and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim, who argue that we are moving into a new period of modernity that has as its main features a highly atomized form of individuality that they call individualization. In this context, class affiliation and social status become less important. And instead of engaging in a battle for access to resources, we find we are engaged in all sorts of activities intended to minimize our risks. They call this "the risk society." In a sense, we all become unconscious insurance actuaries, trying to assess what course of action will offer our selves and our children the greatest chances to survive, and we might even hope — on a good day — thrive.Rather than condemn individuals for their use of psychopharmacological interventions, Miller and Leger analyze these trends within a particular moment of late modernity, in which individuals are urged to work on themselves, and their children, to remain ever marketable — as human capital.

As a parent who is actively engaged in such assessments — and who among us isn't? — keeping Sweet M on the Focalin was a no-brainer. Beyond the fact that Sweet M is regularly monitored for changes in her blood pressure (a possible side effect of the stimulant medication), the reality is that the FDA's decision to black box these medications was not based on any new evidence or new studies.

While I might long for a world where my daughter could thrive without either of the medications she takes, we certainly do not inhabit such a world now, nor can I expect that we will we anytime soon. My own tendency to want to resist or refute the medical protocols of our day are mitigated by my parental desire to create the best possible life for my child in a world where the odds are already stacked against her.

And so while it's a bit odd to think of parenting as a risk assessment exercise, I'm afraid that the Becks, Miller, and Leger are probably correct: we're constantly calculating the odds and aiming for the best outcomes.

May we continue with the finest information, our very best possible judgment, and the most beneficial outcomes for all.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • parenting • Ulrich Beck • Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim • Toby Miller • Marie Claire Leger • risk society • Ritalin

9 comments:

Excellent post. I like the point of view and will check out the book.

I think this should be referenced in my post today as I raised the Ritalin question.

Estee

Wonderful!

As I said on Estee's blog earlier today, I take medication to help me control my symptoms, so that I can be more effective and have less anxiety. (I am now on Strattera, which is a non-stimulant, because the Ritalin family either increases my anxiety or doesn't work, and the Dexedrine family causes me sleep disturbances.) My goal (as someone who was diagnosed only last year) is to use meds to help me be able to focus enough that I can learn the skills that I missed learning when I was small, so that maybe someday I will be able to do well without medication. That day may never come, but that's okay. It's my choice, and I would do the same for a child in my care. (I went into more detail on Estee's blog.)

"Serendipity" that you should post on this as we are in one of those periods of reconsidering over what's going on in Charlie's education/therapeutic/medical profile. The best strategy for us has been an interdisciplinary one that combines medical strategies "traditional" and "biomedical/alternative," all with the goal of getting Charlie to be the best that he can be in the classroom. It's tough as, like you, I feel a tug about giving him medication but it is never done without much thought and consideration of tons of angles.

I always call myself on myself when I feel any "ideology"---any set theoretical or philosophical framework--imposing itself on Charlie's needs. It has been the case many a time that what my humanist beliefs would like to see happen is not the same as what Charlie needs. Raising Charlie has been about seeing where there are cracks in my own thinking that I need to seal up, to do what is best for Charlie according to Charlie.

As for risk, my friend----there are reasons we keep pillows in strategic places and (and here fear has to cope with Doing What's Best), who knows, a helmet.

Thanks Estee and Jannalou and Kristina, I'm glad if this post was helpful. I spent nearly a month thinking about the FDA black box warning and I'm still wondering what actually precipitated it: fallout for dropping the ball on Vioxx and then Merck gets off scott-free in court? It's just a little difficult to understand what goes on at the FDA . . .

A close relative of Sweet M's was Dx'd with ADHD in his mid-thirties and spent several years just mourning all the lost opportunties of his childhood when he realized how different the world could be when he could attend and focus . . .

I don't want Sweet M to have that experience of having to try to play catchup regarding *years* of skills, information, and knowledge.

I don't want Sweet M to have that experience of having to try to play catchup regarding *years* of skills, information, and knowledge.

On my really bad days, I play the "what if" game:

"What if" I'd been on meds when I was in elementary school? Would I have had more friends?

"What if" I'd been on meds when I was in junior high? Would I have been a happier pre-teen?

"What if" I'd been on meds when I was in high school? Would I have done better when the work got harder?

"What if" I'd been on meds when I was in University? Would I have done better across the board?

But then it gets into this:

"What if" I'd been diagnosed as a child, instead of as an adult? Would I have spent six years working with autistic children? Would I understand the perils & difficulties facing autistic people and others who have disabilities as well as I do? Would I be able to 'birth' projects as fully formed as I do?

I don't know. Nobody does. There is no way of knowing.

I would like to be able to monitor myself a bit better than I do. And I wouldn't mind having better social skills.

But there's no guarantee that having been diagnosed as a child (especially in the late 1970's and early 1980's) would have gotten me the treatment I needed in order to learn the skills I didn't learn "normally". (In fact, it's very likely that it wouldn't have happened at all.)

As parents we are constantly thinking about what is best for our children. If we are indeed giving them the best platform to be successful. Our ASD children bring with them many more complicated and unaided decisions. Many more roads that not only pitchfork, but have dead ends that never provided the aide of a map. I admire how "on top" of sweet M's medications you are. It sounds really confusing and ever changing. I hope by reading your posts I can at least get a glimpse of one of the roads that was successfully taken.

Kristin

"While I might long for a world where my daughter could thrive without either of the medications she takes, we certainly do not inhabit such a world now, nor can I expect that we will we anytime soon. My own tendency to want to resist or refute the medical protocols of our day are mitigated by my parental desire to create the best possible life for my child in a world where the odds are already stacked against her."

My personal opinion is that it's better to fight an unjust system than give in to it, even if the consequences of that choice are quite serious. However, I also think that, if possible, it should be Sweet M's choice. I don't know what I'd do as a parent. Probably simply avoid situations requiring my child to take meds, such as homeschooling my child or looking for some alternative school that fits better with my child's learning style.

But as I'm not a parent, I don't know whether my idealistic opinions are really feasible.

Ettina, Thanks so much for your comment. The dialogue between folks in the spectrum and parents of kids in the spectrum, whether NT or not, is a very very valuable one. I really look to adults in the spectrum for advice and guidance on what helped them.

And I think balancing idealism and so-called realism is a very tough call.

And medication is a hot button issue for so many people, especially for parents of kids in the spectrum.

I don't think that for our family that homeschooling could provide Sweet M with the best possible learning opportunities . . . I am not the ideal teacher for her all day long, even if I didn't need to earn a living. And, a daresay that her father probably isn't either.

School is another setting that allows her to have space, access to resources, access to other kids -- should she want to socialize -- and usually very well-trained and loving educators. Her school is a resource, a collective resource, not a prison.

Without her medication, Sweet M was flipping out 3-5 times a day . . . whether she was in school or not. And when I say flipping out, I mean losing access to any pleasure, joy, information, learning, or fun for long period of time. Long = hours. She was suffering.

Even as a girl of very few words at the time (age 4) , Sweet M told me that she hated herself because she couldn't stop thinking about talking on a particular telephone in an airport we passed through. So, in the end, while I do long for a world where meds weren't so important for so many people, I can't imagine making her suffer as we try to make or find that world.

Also, sometimes I wonder if the longing for a "natural" solution might not be a kind of pastoral nostalgia for a "simpler time" etc etc. I am especially struck by the fact that so many autistic adults -- I'm thinking Temple Grandin and Donna Williams here -- speak positively about meds that helped them.

As for autonomy, Sweet M's psychiatrist always asks her what she thinks about the medications, if she feels better with them, and so on.

While I think the idea of "choice" in a child who has been medicated for a couple of years already is a bit illusory, I think we all want her to have her own autonomy . . . to the extent that any of us actually has autonomy.

Thank you. Thank you for your optimism and idealism. We all need it.

Post a Comment