Saturday, February 25, 2006

Cultivation

On the heels of my thinking about "oughtism," I'm drawn to thinking about its inverse: repressive tolerance.

The idea of repressive tolerance, developed by twentieth century political philosopher Herbert Marcuse, is that sometimes actions that appear to be about freedom and human liberty are actually repressive. Some behaviors that we tolerate in ourselves, and in others, in the name of freedom, may actually be detrimental to us individually and collectively. Or, put differently, what looks like freedom may be a pleasant, pleasurable prison.

Marcuse's examples, from 1965, included allowing advertising and publicity to dumb-down our thinking, or allowing automobiles to transform the landscape of our cities, making pedestrians an endangered species. In the name of freedom, and especially in the name of free markets, we've come to allow all kinds of ills, from environmental havoc to electoral travesties. In the name of sexual freedom we have, perhaps, created vacuous forms of sexual expression that lack any sense of human connection. For Marcuse, while these "freedoms" look like some sort of liberation, they're actually repressive in that they limit the sort of genuine human flourishing that he envisioned.

Consumer culture is particularly prone to encouraging repressive tolerance. For example, that "one more donut" might feel like it was your choice, but it might also have just been because a marketing genius at Dunkin' Donuts figured out that they should pipe the smell of donuts out of their shops to snag us all by the primal sense of smell.

So what does this have to do with oughtism, autism, and raising Sweet M?

While I hope for liberation from oughtism, I sometimes wonder if my willingness to go with the flow with Sweet M constitutes a kind of repressive tolerance born of parenting fatigue. It's often so hard to know when to push and when to back off.

Even for parents of typically developing children there are questions of when to discipline and when to leave well enough alone, but for autism and ADHD parents, the stakes are arguably higher, and the possibilities for parental fatigue that much greater. After one gets done slaying the dragons around the IEP conference, or the Board of Education's bus schedules, or the school placement — not to mention earning a living adequate enough to support the services our kids need — how much energy remains for reigning in our kids?

While there are many non-negotiables in Sweet M's world: no hitting, no screaming, must do homework, and so on, she also has a huge amount of freedom in, for example what she eats. She really doesn't like much of anything that isn't pasta, sweets, or milk products. She may very well have a gluten-casein sensitivity, but I haven't had the heart to go through a rotation diet with her. Controlling her food reminded me much too much of battles over food, eating, and body image with my own mother. So she eats pretty much what she wants — a hi-carb, hi-sugar diet very similar to that of high-functioning autistic genius Andy Warhol — and she takes a megavitamin (non-negotiable).

We have allowed many of our parenting decisions to be governed by her preferences, and I sometimes wonder how wise that is. What are real preferences — that ought to be honored — and what are the passing whims of an eight year old?

I think about one of the hot-button issues among autism parents and autism activists—how to handle our kids' stims. If we believe what autistic authors such as Donna Williams and Temple Grandin say about stimming, then letting our kids remain transfixed by rituals or other stereotypies, would be repressive, in that it would not be allowing them access to their human freedom. But, on the other hand, having some sort of self-soothing behavior, which they also describe stimming as being, can aid in regulating internal states.

How do we balance between oughtism — shoehorning them into shapes that are too far from their natural inclinations — and letting them run too wild, too far a field, too uncultivated?

I wish I knew.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • parenting • repressive tolerance • Herbert Marcuse

Friday, February 24, 2006

Oughtism or Sweet Dreams

Since we were staying in a motel on our little mini-vacation in Hershey, PA, we found ourselves eating dinner out a couple of nights, which is something that we rarely attempt in the city. This proved to be the most challenging part of the trip because Sweet M's olfactory sensitivities make so many food odors disgusting for her.

The first night, in an Italian restaurant with overpriced and barely edible food, Sweet M was squirming, grimacing, getting up out of her seat, and demanding, "Ewww, get it away, get it away" when our pastas with a slightly garlicky tomato sauce arrived. The second night, at a different restaurant, M jumped up when my tomato soup arrived and seated herself at an adjacent table — upwind, I suppose, from the offending odor.

Sweet M's father was deeply annoyed by M's restaurant (mis)behavior. It's easier for me to empathize with her olfactory sensitivities as I have the advantage of having had overpowering morning sickness when I was pregnant with her. That is, I have a relatively recent and visceral memory of how affecting olfactory disgust can be. But for M's father this was becoming a quality of life issue. "We have to be able to eat in a restaurant," he said. "She's got to grow up and learn some manners." And, admittedly, the behavior was awfully annoying.

This got me thinking about some of the times in Sweet M's life that I'd decided that something just ought to be a particular way. There are only a couple of examples of this, as I'm not much for imposing my will in the face of overpowering resistance on M's part. Most of the few times that I've taken such a stand, I've lived to regret it.

Take the case of bedwetting. Sweet M has enuresis, the medical word for bedwetting. Sometime in her kindergarten year — with an eye toward the sleepovers that might be on the horizon in elementary school — I decided that the bedwetting had to come to an end. Her longtime babysitter, a woman who's raised five children and an even larger number of grandchildren, agreed that it was time. M's pediatrician thought it was time as well.

And so we had Sweet M start sleeping without "diapies," as she affectionately called them.

About five nights a week she could get through the night without wetting the bed. But the other two nights the bed was soaked, which interrupted her sleep.

Less important, but not insignificant, was the fact that I was saddled with pounds of extra laundry. If we lived in a suburban house with a washer and dryer, it might not have been so bad. But since laundry for us means schlepping out to the laundromat and paying $2.00 a load for washing and up to $4.00 for the dryer (depending on the drying time), this was a costly and time-consuming undertaking.

Also, because M was still greatly in need of sensory stimulation, we'd let her jump on the bed, which would put small tears in the mattress cover, which would then leak and spoil the mattress. It was a mess, all around. I was spraying the mattress with those odor-killing sprays and schlepping to the laundromat, and basically devoting about 6-10 hours a week to this project of nighttime toilet training.

We persisted on this course for nearly a year. We never scolded her about wetting the bed since we didn't want to make a huge deal out of it, but it was tiresome. She wanted the bed to be dry every bit as much as I did, but we just weren't getting there. Every once in a while we'd go a week without a bedwetting incident, but that was the exception, not the rule.

M's psychiatrist suggested a medication for enuresis, but I didn't want her on an additional medication for something as unimportant as bedwetting.

M's psychiatrist suggested a medication for enuresis, but I didn't want her on an additional medication for something as unimportant as bedwetting.

M herself was patient with our experiment in nighttime toilet training, but one day, after she'd wet the bed four nights in a row, I said, "Oh M, what do you think we should do?"

She paused for a moment, put her finger to her head, and said, "I know. Let's get diapies!"

I mumbled something about let's see if you can get through the night since you're getting to be a big girl, no?

Okay, she'd said, resigning herself.

I became a little obsessed with bedwetting, discussing it with many friends. I learned, to my surprise, that two of the most accomplished women I know — one a professor at a major university, the other a prominent psychologist is the city — both wet their beds until puberty. Sometimes the brain — even the most able of brains — just isn't ready to sleep through the night dry.

Nighttime continence requires both a hormonal function and some kind of bladder control during sleep. Apparently in some children a natural anti-diuretic hormone released at sunset condenses the urine at night, making bladder control easier. In other children, this hormone is absent, making dry nights more challenging, if not impossible. Like so many things, this is not a simple matter of willpower.

About a year ago we changed pediatricians. M's first pediatrician had children herself and moved out of the city (which turned out to be a blessing for all of us.)

When we met with our new pediatrician, I brought up the bedwetting problem and she said that there are things you can do . . . there is an alarm system that wakes them up when the bed gets wet, so it trains them, but it's possible that her brain just isn't developed enough yet to manage nighttime continence. Why don't you just get pull-ups for her?

"I thought we should stay the course, and move forward, not backward."

"Look," M's doctor said, "Think of how much easier your life will be. Eventually she'll be dry through the night."

This was one time that I was completely in tune with medical authority. We got the nighttime diapers. While they're by no means inexpensive, the cost is far less than what I was spending on laundry, not to mention in time. Some countries even have programs to subsidize the cost of diapers for kids with developmental differences. Very civilized. (See Sometimes Holland Feels Like Hell, January 7, 2006 if you live in Canada and need incontinence supplies.) But back to our story in New York City, the capital of rugged individualism and self-mastery . . .

The week after we went back to nighttime diapers, I was at school event and M's teacher came up to me and asked, "What have you been doing with M—she's so happy and relaxed and focused this week?"

"Diapies," I said.

"Diapies?" he asked.

"Yes," I said. "We've gone back to having a nighttime diaper and M seems to be sleeping better now."

"Wow," he said. "Well, it's really working."

Why did we struggle for nearly a year, with M never getting a good night's sleep, and me ever schlepping wet bedding to the laundromat, spraying the mattress with Febreze?

I had gotten it into my head that M ought to be able to keep the bed dry. I'd been dreaming about the sleepovers that the little girl of my fantasies would be having with her little friends. She can't be wearing diapers to a sleepover, I'd think. And the people I trusted — her doctor, her babysitter, her father — all agreed that she ought to be able to do this. But the fact was that she couldn't. She just couldn't.

In one of the self-help books that I've read for my other research there is an expression about the word "should." Readers are encouraged to focus on what they want to do, rather than on what they think they should do. One writer tells his readers to stop "shoulding" all over themselves, referencing the very sorts of toileting and self-control issues that we were struggling with.

In the case of this bedwetting problem our "shoulds" and our "oughts" got in our way of seeing what wasn't working for Sweet M. We weren't struggling because of her autism — or whatever it is that goes on for her — we were suffering from "oughtism": the inflexible belief that something oughta be a particular way, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding.

I hope we will all be delivered from oughtism. And arrive in a place where there are sweet dreams for all of us.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • bed wetting • enuresis

The first night, in an Italian restaurant with overpriced and barely edible food, Sweet M was squirming, grimacing, getting up out of her seat, and demanding, "Ewww, get it away, get it away" when our pastas with a slightly garlicky tomato sauce arrived. The second night, at a different restaurant, M jumped up when my tomato soup arrived and seated herself at an adjacent table — upwind, I suppose, from the offending odor.

Sweet M's father was deeply annoyed by M's restaurant (mis)behavior. It's easier for me to empathize with her olfactory sensitivities as I have the advantage of having had overpowering morning sickness when I was pregnant with her. That is, I have a relatively recent and visceral memory of how affecting olfactory disgust can be. But for M's father this was becoming a quality of life issue. "We have to be able to eat in a restaurant," he said. "She's got to grow up and learn some manners." And, admittedly, the behavior was awfully annoying.

This got me thinking about some of the times in Sweet M's life that I'd decided that something just ought to be a particular way. There are only a couple of examples of this, as I'm not much for imposing my will in the face of overpowering resistance on M's part. Most of the few times that I've taken such a stand, I've lived to regret it.

Take the case of bedwetting. Sweet M has enuresis, the medical word for bedwetting. Sometime in her kindergarten year — with an eye toward the sleepovers that might be on the horizon in elementary school — I decided that the bedwetting had to come to an end. Her longtime babysitter, a woman who's raised five children and an even larger number of grandchildren, agreed that it was time. M's pediatrician thought it was time as well.

And so we had Sweet M start sleeping without "diapies," as she affectionately called them.

About five nights a week she could get through the night without wetting the bed. But the other two nights the bed was soaked, which interrupted her sleep.

Less important, but not insignificant, was the fact that I was saddled with pounds of extra laundry. If we lived in a suburban house with a washer and dryer, it might not have been so bad. But since laundry for us means schlepping out to the laundromat and paying $2.00 a load for washing and up to $4.00 for the dryer (depending on the drying time), this was a costly and time-consuming undertaking.

Also, because M was still greatly in need of sensory stimulation, we'd let her jump on the bed, which would put small tears in the mattress cover, which would then leak and spoil the mattress. It was a mess, all around. I was spraying the mattress with those odor-killing sprays and schlepping to the laundromat, and basically devoting about 6-10 hours a week to this project of nighttime toilet training.

We persisted on this course for nearly a year. We never scolded her about wetting the bed since we didn't want to make a huge deal out of it, but it was tiresome. She wanted the bed to be dry every bit as much as I did, but we just weren't getting there. Every once in a while we'd go a week without a bedwetting incident, but that was the exception, not the rule.

M's psychiatrist suggested a medication for enuresis, but I didn't want her on an additional medication for something as unimportant as bedwetting.

M's psychiatrist suggested a medication for enuresis, but I didn't want her on an additional medication for something as unimportant as bedwetting.M herself was patient with our experiment in nighttime toilet training, but one day, after she'd wet the bed four nights in a row, I said, "Oh M, what do you think we should do?"

She paused for a moment, put her finger to her head, and said, "I know. Let's get diapies!"

I mumbled something about let's see if you can get through the night since you're getting to be a big girl, no?

Okay, she'd said, resigning herself.

I became a little obsessed with bedwetting, discussing it with many friends. I learned, to my surprise, that two of the most accomplished women I know — one a professor at a major university, the other a prominent psychologist is the city — both wet their beds until puberty. Sometimes the brain — even the most able of brains — just isn't ready to sleep through the night dry.

Nighttime continence requires both a hormonal function and some kind of bladder control during sleep. Apparently in some children a natural anti-diuretic hormone released at sunset condenses the urine at night, making bladder control easier. In other children, this hormone is absent, making dry nights more challenging, if not impossible. Like so many things, this is not a simple matter of willpower.

About a year ago we changed pediatricians. M's first pediatrician had children herself and moved out of the city (which turned out to be a blessing for all of us.)

When we met with our new pediatrician, I brought up the bedwetting problem and she said that there are things you can do . . . there is an alarm system that wakes them up when the bed gets wet, so it trains them, but it's possible that her brain just isn't developed enough yet to manage nighttime continence. Why don't you just get pull-ups for her?

"I thought we should stay the course, and move forward, not backward."

"Look," M's doctor said, "Think of how much easier your life will be. Eventually she'll be dry through the night."

This was one time that I was completely in tune with medical authority. We got the nighttime diapers. While they're by no means inexpensive, the cost is far less than what I was spending on laundry, not to mention in time. Some countries even have programs to subsidize the cost of diapers for kids with developmental differences. Very civilized. (See Sometimes Holland Feels Like Hell, January 7, 2006 if you live in Canada and need incontinence supplies.) But back to our story in New York City, the capital of rugged individualism and self-mastery . . .

The week after we went back to nighttime diapers, I was at school event and M's teacher came up to me and asked, "What have you been doing with M—she's so happy and relaxed and focused this week?"

"Diapies," I said.

"Diapies?" he asked.

"Yes," I said. "We've gone back to having a nighttime diaper and M seems to be sleeping better now."

"Wow," he said. "Well, it's really working."

Why did we struggle for nearly a year, with M never getting a good night's sleep, and me ever schlepping wet bedding to the laundromat, spraying the mattress with Febreze?

I had gotten it into my head that M ought to be able to keep the bed dry. I'd been dreaming about the sleepovers that the little girl of my fantasies would be having with her little friends. She can't be wearing diapers to a sleepover, I'd think. And the people I trusted — her doctor, her babysitter, her father — all agreed that she ought to be able to do this. But the fact was that she couldn't. She just couldn't.

In one of the self-help books that I've read for my other research there is an expression about the word "should." Readers are encouraged to focus on what they want to do, rather than on what they think they should do. One writer tells his readers to stop "shoulding" all over themselves, referencing the very sorts of toileting and self-control issues that we were struggling with.

In the case of this bedwetting problem our "shoulds" and our "oughts" got in our way of seeing what wasn't working for Sweet M. We weren't struggling because of her autism — or whatever it is that goes on for her — we were suffering from "oughtism": the inflexible belief that something oughta be a particular way, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding.

I hope we will all be delivered from oughtism. And arrive in a place where there are sweet dreams for all of us.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • bed wetting • enuresis

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

Sweet Adventures

Autism activists such as Temple Grandin, Donna Williams, and Valerie Paradiz make the case that rather than trying to eliminate an autistic person's preoccupations, that these areas of hyperfocus ought to be cultivated — used to expand learning and future career opportunities.

And that is why, this week, we find ourselves in Hershey, Pennsylvania, the birthplace of Milton Hershey and the home of Chocolate World. Yes, Sweet M is fond of sweets, and none more than chocolate.

I'm hoping, of course, that vacationing with a chocoholic at Hershey World isn't akin to encouraging an alcoholic to take a tour vineyards and get a job at a winery.

In our two days here we've gone on the trolley tour of the town of Hershey, where Chocolate Avenue's street lamps are shaped like Hershey's Kisses and there is a perennial scent of chocolate in the air downwind of the still-operating factory. We've seen a documentary about the cultivation of the cacao bean in the equatorial climate of South America and Africa. We watched the 3-D cartoon extravaganza promoting all of Hershey's products. We visited the Milton Hershey Museum to learn about Hershey's life.

And M had the Hershey Factory Experience: she packed Kisses into a gear shaped plastic box and delivered them to the conveyor belt.

After she'd put her box of chocolates on the conveyor belt, the chocolate factory "supervisor" said that M would make a great factory worker. I couldn't help but hope that I can set my sights a little higher for her. Industrial chocolate making is backbreaking work, or so the Hershey Museum says . . . .

The Hershey Museum also offers the story of Milton Hershey's life. Hershey was an interesting character. Although he is counted among America's tall tales self-made success, he had several business failures before finally succeeding with his Crystal Caramel Company. In other words, his road to success was paved with failure after failure.

After his fourth candy business failure, Hershey had borrowed money from an aunt, who had mortgaged her house to finance his final caramel company. Fluctuating sugar prices were, once again, threatening to put his company out of business. The bank was just about ready to foreclose on his aunt's house when a British company ordered all the caramels he had in stock, and then some. Hershey's fortune was made, and within a couple of years he sold his successful caramel company to invest in the even riskier chocolate business. Or at least that's the story the tour guide told us.

Another story had Hershey borrowing the money to start his last caramel business from a former employee who'd worked in his Philadephia candy shop. It's not easy to get the real story behind these layers of choco-mythology.

But what struck me about the overall Hershey story was the fact that this quintessential self-made man was actually "made" by the support that he had from his family . . . from his aunt who was willing to put everything on the line for him to his former employee, depending on who you believe.

How like our kids all this seemed to me: so many failures on the road to basic successes, successes that are buttressed by our willingness to mortgage, figuratively, and sometimes literally, everything we have.

One hopes the investment will pay off, but there are no guarantees and you have to just keep trying everything. Hershey moved from Derry, PA to Lancaster to Philadelphia to Denver to New York and back to Lancaster, then on to Derry, PA in his quest for success. Austim parents who have the means — and some who don't — move their kids all over the country in search of school districts and medical centers with appropriate programs.

Like Hershey, you have to call in all your favors—from family, friends, and even former employees—to get what you need for your kid.

And in the end, you just hope that it will all work out, somehow sweet.

Our trip to Hershey has been.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • family vacations • Temple Grandin • Donna Williams

Wednesday, February 15, 2006

Five-Star Autism Reading

Christine (of Day Sixty-Seven) wanted to know which autism books rate five-stars in my book. Since there are dozens of books that I haven't yet read, both from the stack on my shelf, and also pouring out of the publishing houses, this may be premature. But here goes . . . a 5-star list to date . . .

Three favorite autie parent memoirs, not counting the blog memoirs that many of you are writing:

The Siege: A Family's Journey into the World of an Autistic Child

by Clara Claiborne Park

What is most dazzling about Park's 1967 memoir is that she bucked the medical wisdom of her time—she lived through the era of the "refrigerator mom" theory—and kept her daughter at home with their family. While the psychiatrists of the time were telling her that it was Clara's supposedly cold and impersonal nature that was creating her daughter Elly's autism, Park—with a trail blazing courage—quietly ignored them. Trust me, there is nothing cold and impersonal in this book. It's a classic.

Exiting Nirvana: A Daughter's Life with Autism

by Clara Claiborne Park

In the 2001 follow-up to The Siege, we learn how Jessy (aka Elly) fared with the incredible support provided by her mom, her family and their community. She is an artist with a three-year waiting list for her work. Here the happy ending is not a "cure"—but a life a meaningful life in the midst of community.

Elijah's Cup: A Family's Journey into the C0mmunity and Culture of High-Functioning Autism and Asperger's Syndrome

by Valerie Paradiz

Paradiz captures not only the story of raising her autistic son Elijah, but also the emergence of the autism rights movement, and the implications of that movement for how we see our children. Rather than seeing them as "damaged" or "defective" or "diseased," Paradiz models how we can elaborate and celebrate their differences and find ways to create robust and expansive communities for them, for ourselves and for each other. After reading book after book about curing-saving-rescuing my child (titles that are probably familiar to you) Paradiz offered a new way of thinking about autism—through a social justice lens. And if that weren't enough, she writes beautifully. This book is a gift.

Then there are the many books by autistic authors that have come out in the past several years. Donna Williams is probably the most famous autistic individual in the world. With nine published books—many of them bestsellers—she could take almost every spot in a top ten list. I've read about half of them, and found them all helpful:

Somebody Somewhere: Breaking Free from the World of Autism

Like Color to the Blind: Soul Searching and Soul Finding

At the moment I'm reading two of Williams's text books: Exposure Anxiety: An Exploration of Self-Protection Response in Austim Spectrum and Autism and Sensing: The Unlost Instinct, and expect that they will be equally helpful in understanding Sweet M's relationship to the world. And I'm looking forward to reading her newest memoir, Everyday Heaven: Journeys Beyond the Stereotypes of Autism.

Like Donna Williams, Temple Grandin is a renowned autistic woman with several bestselling books, among them, Thinking in Pictures: And Other Reports from My Life with Autism and Animals in Translation: Using the Mysteries of Autism to Decode Animal Behavior (written with Catherine Johnson).

While working on this list I was surprised to realize that I haven't yet read her earliest book: Emergence, Labeled Autistic. I think I'll try to pick up a copy today. Also, Grandin's mother, Eustacia Cutler, has a book just out called A Thorn in My Pocket: Temple Grandin's Mother Tells the Family Story, and that book is definitely on my "to read" list.

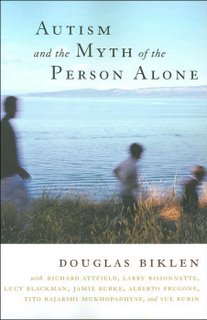

Autism and the Myth of the Person Alone, edited by Douglas Biklen with contributions from a variety of autistic individuals, including Richard Attfield, Larry Bissonnette, Lucy Blackman, Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyay, and Sue Rubin. Reading about the world from the perspective of these autistic writers has been as helpful as anything I've read by a medical professional.

Autism and the Myth of the Person Alone, edited by Douglas Biklen with contributions from a variety of autistic individuals, including Richard Attfield, Larry Bissonnette, Lucy Blackman, Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyay, and Sue Rubin. Reading about the world from the perspective of these autistic writers has been as helpful as anything I've read by a medical professional.

Finally, two books that I love because they've helped me understand the implications of the social constructions of disease and disability . . .

Life As We Know It: A Father, A Family, and an Exceptional Child, by Michael Bérubé. As a professor of comparative literature and cultural studies, Bérubé turns his knowledge of these fields to the task of understanding life with his Down Syndrome son. That might sound boring, but it's not. Believe me, it's amazing. He covers everything from our aversion to "feeble mindedness" to the problem of prenatal testing and the elective termination of Down Syndrome pregnancies.

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman. Fadiman tells the story of how cultures collide—with disasterous results—over the body and soul of a young Hmong/Laotian girl with epilepsy. Among the Hmong, Lia Lee's epilepsy is viewed as a sign of her special connection with the spirit world. But in the Merced, California community where her family lands as refugees from from the disasterous debacle of the American-Indochinese War (aka the Vietnam war), Lee's epilepsy is viewed as an illness to be treated. When the medical community requires that Lia be removed from the loving care of her family, calamity results. If you ever had any doubt that diseases are social constructions, then read this powerful account.

That's my current list of favorites, with an emerging list of others to read. What are yours?

Note to readers: If you click on the text links for titles, you'll land at Amazon. If you click on the pictures, you'll land at Barnes and Noble. Some readers don't shop at Amazon because CEO Jeff Bezos gives so much money to the Republican party. And some readers don't shop at B & N because CEO Leonard Riggio supports the Democrats. You pick. Personally, I like to use the public library.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • learning disabilities • special education

Three favorite autie parent memoirs, not counting the blog memoirs that many of you are writing:

The Siege: A Family's Journey into the World of an Autistic Child

by Clara Claiborne Park

What is most dazzling about Park's 1967 memoir is that she bucked the medical wisdom of her time—she lived through the era of the "refrigerator mom" theory—and kept her daughter at home with their family. While the psychiatrists of the time were telling her that it was Clara's supposedly cold and impersonal nature that was creating her daughter Elly's autism, Park—with a trail blazing courage—quietly ignored them. Trust me, there is nothing cold and impersonal in this book. It's a classic.

Exiting Nirvana: A Daughter's Life with Autism

by Clara Claiborne Park

In the 2001 follow-up to The Siege, we learn how Jessy (aka Elly) fared with the incredible support provided by her mom, her family and their community. She is an artist with a three-year waiting list for her work. Here the happy ending is not a "cure"—but a life a meaningful life in the midst of community.

Elijah's Cup: A Family's Journey into the C0mmunity and Culture of High-Functioning Autism and Asperger's Syndrome

by Valerie Paradiz

Paradiz captures not only the story of raising her autistic son Elijah, but also the emergence of the autism rights movement, and the implications of that movement for how we see our children. Rather than seeing them as "damaged" or "defective" or "diseased," Paradiz models how we can elaborate and celebrate their differences and find ways to create robust and expansive communities for them, for ourselves and for each other. After reading book after book about curing-saving-rescuing my child (titles that are probably familiar to you) Paradiz offered a new way of thinking about autism—through a social justice lens. And if that weren't enough, she writes beautifully. This book is a gift.

Then there are the many books by autistic authors that have come out in the past several years. Donna Williams is probably the most famous autistic individual in the world. With nine published books—many of them bestsellers—she could take almost every spot in a top ten list. I've read about half of them, and found them all helpful:

Somebody Somewhere: Breaking Free from the World of Autism

Like Color to the Blind: Soul Searching and Soul Finding

At the moment I'm reading two of Williams's text books: Exposure Anxiety: An Exploration of Self-Protection Response in Austim Spectrum and Autism and Sensing: The Unlost Instinct, and expect that they will be equally helpful in understanding Sweet M's relationship to the world. And I'm looking forward to reading her newest memoir, Everyday Heaven: Journeys Beyond the Stereotypes of Autism.

Like Donna Williams, Temple Grandin is a renowned autistic woman with several bestselling books, among them, Thinking in Pictures: And Other Reports from My Life with Autism and Animals in Translation: Using the Mysteries of Autism to Decode Animal Behavior (written with Catherine Johnson).

While working on this list I was surprised to realize that I haven't yet read her earliest book: Emergence, Labeled Autistic. I think I'll try to pick up a copy today. Also, Grandin's mother, Eustacia Cutler, has a book just out called A Thorn in My Pocket: Temple Grandin's Mother Tells the Family Story, and that book is definitely on my "to read" list.

Autism and the Myth of the Person Alone, edited by Douglas Biklen with contributions from a variety of autistic individuals, including Richard Attfield, Larry Bissonnette, Lucy Blackman, Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyay, and Sue Rubin. Reading about the world from the perspective of these autistic writers has been as helpful as anything I've read by a medical professional.

Autism and the Myth of the Person Alone, edited by Douglas Biklen with contributions from a variety of autistic individuals, including Richard Attfield, Larry Bissonnette, Lucy Blackman, Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyay, and Sue Rubin. Reading about the world from the perspective of these autistic writers has been as helpful as anything I've read by a medical professional.Finally, two books that I love because they've helped me understand the implications of the social constructions of disease and disability . . .

Life As We Know It: A Father, A Family, and an Exceptional Child, by Michael Bérubé. As a professor of comparative literature and cultural studies, Bérubé turns his knowledge of these fields to the task of understanding life with his Down Syndrome son. That might sound boring, but it's not. Believe me, it's amazing. He covers everything from our aversion to "feeble mindedness" to the problem of prenatal testing and the elective termination of Down Syndrome pregnancies.

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman. Fadiman tells the story of how cultures collide—with disasterous results—over the body and soul of a young Hmong/Laotian girl with epilepsy. Among the Hmong, Lia Lee's epilepsy is viewed as a sign of her special connection with the spirit world. But in the Merced, California community where her family lands as refugees from from the disasterous debacle of the American-Indochinese War (aka the Vietnam war), Lee's epilepsy is viewed as an illness to be treated. When the medical community requires that Lia be removed from the loving care of her family, calamity results. If you ever had any doubt that diseases are social constructions, then read this powerful account.

• • •

That's my current list of favorites, with an emerging list of others to read. What are yours?

Note to readers: If you click on the text links for titles, you'll land at Amazon. If you click on the pictures, you'll land at Barnes and Noble. Some readers don't shop at Amazon because CEO Jeff Bezos gives so much money to the Republican party. And some readers don't shop at B & N because CEO Leonard Riggio supports the Democrats. You pick. Personally, I like to use the public library.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • learning disabilities • special education

Sunday, February 12, 2006

Reading 101

Sweet M's IEP for the current school year calls for her to be reading at a K.5 level by the end of the year—the end of what would be second grade, if we were counting.

Sweet M's IEP for the current school year calls for her to be reading at a K.5 level by the end of the year—the end of what would be second grade, if we were counting.As disappointing as this goal was to me—chronic reader that I am—it seemed appropriate enough since she wasn't reading at all last year. But as a person who makes my way through life reading, the idea that my daughter might not ever read at all, let alone read with pleasure, was weighing heavily on me.

Although I know M has been doing better in reading since we recognized that this was a reading emergency and started a sight word program at home, I was curious as to how her teachers thought she was doing and was looking forward to the parent-teacher conference.

M, the teachers reported, is now reading at an early first grade level. She's done a years worth of reading instruction in four months.

Her reading teacher described how she—the reading teacher, not Sweet M—started to cry in a recent reading lesson because M had gone from reading nothing at all to reading full paragraphs in a matter of days. Seeing something like this, she said, is the reason you do this sort of work.

Although I will probably forever wonder why M spent two years struggling—herself crying—with the Wilson Fundamentals reading program before her teachers switched to a sight reading program combining the Swain and Merrill approaches, I am grateful that she is, at last, learning to read.

M has taught us that she is completely capable of learning to read—once we learned how to teach her.

That got me thinking about how much more I learn about her every day. Every time I think I have a handle on her ASD-ADHD-OCD-ODD-PDD, NOS I learn something new.

The latest thing I've learned is that M, though fairly well coordinated, has a visual problem with what her eye doctor calls "crossing the midline." When she was having her eyes examined recently, the eye doctor asked her to track a light without moving her head. In the process the doctor and I could both see that at the point where the eyes need to track across the center point of the visual field, her eyes stop, ever so slightly, until she can refind the spot. Her right and her left brain don't communicate with each other with the ease that we NTs apparently have. And, of course, this can have implications for ease of reading because it will be difficult to keep your place if you lose your focus or tracking right at the center of your visual field.

This anomaly would also explain a rather astonishing result on her recent neuropsychological tests. On a test of fine motor skills called the Purdue Pegboard test, Sweet M, to my complete surprise, scored in the lowest percentile (<1) when asked to put pegs in a pegboard with her right hand (her dominant hand) and left hand separately. Since fine motor skills have never been a huge problem for her, this was shocking.

But what was really amazing was that when asked to perform the test using both hands at the same time, she scored in the 61st percentile, or slightly above normal. What to make of this? I'm not completely sure, since I didn't see the test protocol, but my guess is that when she had to cross the midline (use her right hand to perform a task on the left side of her visual field) that it was nearly impossible for her to do the task. But when she could use both hands, it was a breeze.

All of this reminds me of a book that was popular back when I was in college: Julian Jaynes's The Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Jaynes's book was controversial at the time, and isn't tremendously fashionable now, but essentially he argued that consciousness (we might add, NT-consciousness) developed when the mind adapted and started communicating more fluidly across the brains' hemispheres. Perhaps, this suggests to me, that at least some of M's problems with so-called "theory of mind" and language processing have to do with this bifurcation of her brain.

But reading books—my most recent stack is pictured above—and spinning out theories is easy when compared with reading what is actually going on for our kids.

Sweet M has been being tested and retested for more than five years now. How, I asked myself, and I asked her OT as nonconfrontationally as I knew how, could this "crossing the midline" problem have gone unnoticed—not just by the OTs, but by the dozens of others who have examined her over the course of these years.

Well, her OT said, probably because we couldn't get her to follow the directions, so we couldn't fully test her. In short, we couldn't read her because we couldn't reach her.

We have to reach farther. We have to read more carefully.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • learning disabilities • special education

Thursday, February 09, 2006

Report Card

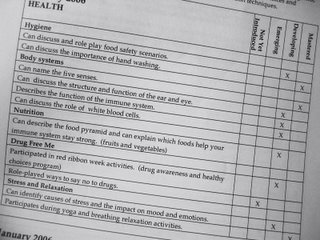

Today is Sweet M's parent-teacher conference. I've been reviewing her report card in advance of the meeting, trying to decode the document and figure out what I should be pushing for and what I should be doing at home.

These report cards aren't like any that I received in school . . . they're 25-30 pages long, with detailed reporting on various subskills. So, for example, a writing skill like "Uses capitalization appropriately" is noted as "emerging," "developing," or "mastered." Behavioral issues, such as "Listens and respects others' points of view" are recorded as "needs improvement," "consistent progress," or "excellent."

But the funniest things in this report card is from the health class. One of the skills in that reports is "Can discuss the importance of handwashing." It is one of two skills the section that she has been marked as "mastered."

Ask an OCD kid to discuss the importance of handwashing and you can almost cut right through the language disorder.

At the conference on teaching Aspie kids that I went to two weeks back, Valerie Paradiz talked about building on Aspie kids' preoccupations as a way of extending learning: use what they love as point of departure for other learning. So a child who is preoccupied with maps becomes an expert on all kinds of geographical information, not just place names. And a girl who is hyperfocused on hamsters develops an experiment with her hamster family.

This suggests something that I've always loved in the philosophy of Georg Simmel: that if you look at any particular thing closely enough, thoughtfully enough, patiently enough, that you can unfold the secrets of almost anything. That goes for our autie kids too.

from Georg Simmel, The Philosophy of Money, page 55

Now off to the parent-teacher conference. I'll let you know how it goes.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • learning disabilities • special education

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

Scanned, or Scammed?

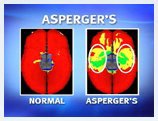

Brain scan images from the Dr. Phil show.

Two weeks back, just after the Dr. Phil show on Asperger's and Tourette Syndromes, Sweet M was scheduled for a check-up with her psychiatrist. While we were there, I mentioned the Dr. Phil show, with the brain imaging slides. I guess I was wondering if we ought to be thinking about some brain scans for Sweet M.

Dr. B's response surprised me, and I'm guessing that it would also surprise Dr. Phil's viewers, so I'm going to share it with you.

When I mentioned that the Dr. Phil show had announced itself as offering new treatment options when all the show seemed to offer were new diagnostic tools in the form of brain scans, Dr. B interrupted.

"But they're not even that," Dr. B said, "They're not that new, and they're not even good diagnostic tools because we just don't have enough data yet to be able to use them diagnostically. What these places [he named two brain scan centers] are doing," he said, "is charging people $7000-9000 for pictures of their brains or their kids' brains, for images that don't really tell you much of anything."

Dr. B works at very prestigious medical research institute himself, so I'm inclined to trust his opinion about such matters.

An article in Sunday's New York Times (2/5/06) suggests nearly the same degree of skepticism about brain scans—not at the level of individual diagnosis, but at the level of contributing to our overall knowledge of brain function:

All of this suggests to me that the Dr. Phil segment on Asperger's was more of an hour-long infomercial for brain scan providers than a show exploring the challenges that families with Asperger's face."Any new method in neuroscience is powerful in terms of evolution of the field only insofar as it tells us that something we thought we knew is wrong," said Dr. J. Anthony Movshon, director of New York University's Center for Neural Science. So far, he said, brain imaging has not done that.

The technology, he said, though now central to brain science, "is in one sense disappointing, in that so far it has told us nothing more than what a neurologist of the 19th century could have told you about brain functions and where they're localized."

And that may be where the hazard lies. The brain's increasingly popular image is a fascinating prop, a colorful as well as useful map, but so far it provides only the illusion of depth (emphasis added).

And given the high-costs associated with raising kids in the spectrum, the last thing we autism parents need is another costly test that has dubious diagnostic value.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • parenting • Dr. Phil • brain scans

Sunday, February 05, 2006

Brian & Max & M & Susan

Last night M and I were hanging around engaged in our own version of parallel play: she was playing on my computer and I was lying around on the bed reading a book.

Last night M and I were hanging around engaged in our own version of parallel play: she was playing on my computer and I was lying around on the bed reading a book.We do a lot of parallel play in our household: there are times when I'm on my computer, and F is on his, and M is watching the television with the headphones on. The completely cyborg family, plugged into our various virtual worlds.

But last night we stepped out of this in the most unexpected way, via the medium of the telephone.

I noticed M had started playing with my home office phone, so I took the other phone and called her.

Hello, is M home?

No, she replied, feigning a British accent, M is out.

Railly, Miss M's out? I said, also affecting a British accent. Where has she gone?

She's out—on a date—she said, emphatically.

A date? Railly? And with whom has she gone on a date?

With Brian.

She's gone on a date with Brian? Why that's splendid! And wherrrre have they gone?

They've gone to the park. They're sitting on a bench . . . kissing.

Oh my, they're kissing. Well, that sounds very very . . . grown-up.

Yes, they're kissing. And Susan came over and she is the most be-u-ti-ful girl and Brian went with her.

Oh my. That sounds awful. How did M feel about that?

M was sad—very sad. But then Max came and she went with Max.

Raillly? She went off with Max.

Oh yes . . . and they went to the carnival.

Oh splendid. And what did they do there?

They went, she said, in the tunnel of luvvvvv.

And on and on and on the narrative went. Soon M was back with Brian because Arnold came along and broke up Brian and Susan.

I was reminded of an R-rated movie called Bob & Ted & Carol & Alice that I never saw because I was too young when it came out. If M's narrative continued much further we'd soon be getting into the restricted rating.

Then, growing tired of storytelling, she shreiked: April fools april fools april fools. I tricked you. Happy pranks day happy pranks day.

Fiction. The girl is writing fiction. Steamy romance novels, if I have the genre correct. Unlike the memoir author so recently dragged through the mud, Miss M seems to have clear ideas about fiction and nonfiction.

And this is the child with social deficits.

So how did this flood gate of narrative open from the girl with the significant expressive language disorder.

My guess is that it was because we weren't looking at each other . . . we were talking to each other on the phone, sitting in the same room, but looking in opposite directions. There was no nonverbal communication to understand, just the narrative, her own narrative of Brian & Max & M & Susan, and it was play.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • learning disabilities • James Frey

Saturday, February 04, 2006

Refuse

Reading Kristina Chew's post about the excrement that is dished out to us and our kids in a culture that thinks of cognitive and neurological dysfunction as "unclean," has helped me realize why I am so resolute—perhaps even obsessive—that M not be derailed from her spectacular progress this year.

Last year, in the midst of Sweet M's most egregious meltdowns, some folks at her school suggested that we look at another school which they thought might be more appropriate. I had looked at many, many schools when M was in the year between nursery school and kindergarten. Given the ambiguity of her diagnoses, I had focused my attention on the LD schools rather than the schools for kids in the spectrum. It was difficult to know what sort of setting would work best for her, with her basically average intelligence overall, and her "splinter skills" in visual perception, her significantly delayed language development, and her temperament (which, in the relative calm of her nursery school setting, had been alright).

M's SEIT (special education itinerant teacher) suggested that M could be okay in a general education New York City kindergarten.

M's speech language pathologist said that a general ed setting would be a disaster.

And the first psychiatrist with whom we met said that we ought to be looking at special ed schools, but she didn't specify exactly what sorts of special ed settings we should seek.

So off I went, focused on "the least restrictive settings." I looked at public schools in our neighborhood, one with a "collaborative team teaching" which is supposed to be the gem of the district. I looked at private, but state-approved (therefore funded), schools for kids with learning disabilities. And I looked at private but unfunded LD schools. It was a busy year. My search was exhaustive. I prepared more kindergarten applications for M than graduate school applications for myself in earlier years. Four times as many.

Some friends without kids, and friends with NT kids, intimated that I was being your typical New York City over-the-top mom. And maybe I was. But I know that in order for my day to go well—in order for me to be able to focus on my professional responsibilities—I have to know that M's day is going okay, too. This wasn't martyr-mom behavior: taking care of my child is a critical part of taking care of myself.

Eventually, through a long process of application and interviews, M was offered a seat at her current school, a state-funded school for kids with language-based learning disabilities and ADHD, but not specifically for kids in the spectrum. In fact, were M to be officially diagnosed in the spectrum, she'd be considered inappropriate for this particular school.

Although last year was a tough one for her, we still thought (and think) that her current school offers her the best possibilities for a rich education and the fullest life opportunities. The teachers are loving and well-trained. The curriculum is flexible. The afterschool programs mirror what is available at general education schools. And the school is picture perfect—the facilities are new and a visual delight, there is rooftop playground, a airy library and computer lab, an outdoor garden, a greenhouse for science projects.

But when the meltdowns were unremitting, M's principal and school psychologist were strategizing with us about other options and met us to look at another program for kids with more challenging issues. Rather than a freestanding school building, the "school" was housed in parts of two floors of a mixed use (office and manufacturing) building. The "library" was several plastic crates of books. The classrooms were dark, and crowded despite the 6:1:1 ratio. The furniture was old, worn, and mismatched–haphazard, disorienting, visually grating.

And as we walked through the hallways, we came across a little boy sitting on the floor unattended. He looked up—right into my husband's eyes—and said, "Help me, help me." I saw F shudder just before an aide came out to coax the little boy back into a class. I suspect that his own childhood experience of strict French military schooling might have been invoked.

We briefly observed a class where a girl around M's age was being congratulated for counting to 4—which is an incredible accomplishment for so many kids, especially for one's put in such unreinforcing settings, but which would not be challenging at all for Sweet M. Then we ran into an occupational therapist whom we knew from M's preschool services—an aggressive and incompetent person who had once tackled M and thrown her to the floor because she wasn't willing to immediately get off an office chair that swiveled. And when I say immediately, I mean immediately. M had been enjoying the chair for all of a minute when she was wrestled to the ground. This person was the head OT for the school.

Now I have to tell you the bad news.

When I'd been initially looking at schools, this one had gotten glowing reports from parents. It is considered a fantastic program . . . a groundbreaking program . . . a gem of a spot for a kid on the spectrum. I hadn't seen it then, because, as I said, I'd been looking primarily at LD schools.

We had a cordial meeting with the head of the school, a woman who was clearly a passionate advocate for autistic kids, and a wonderful and warm person—working 24/7 to try to make a good program for these kids—but offered the refuse of the city as her resources.

When F and I left the school we walked about two blocks in complete silence. I think it would be fair to say that we were speechless. "What do you think?" I eventually asked. He started to speak, to almost stammer a reply. The multilingual man was struggling to find words. So I interrupted him. I don't remember my exact words, but I suspect that they probably started with a stock phrase about stepping over my dead body, or "if-it-were-the-last-school-on-the-planet."

We sent notes to everyone thanking them for their time, concern, and commitment. And we meant it: these are all concerned and committed educators.

And we refused the placement. We have to refuse to accept the refuse, the leftovers, the hand-me-downs, and the outright excrement that's offered to us and our kids. But how do we do that, and still support the educators, like this devoted head of school, who find themselves struggling to create new settings for our kids? That's the really difficult work. How do we take the loads of manure that are thrown at us and use them to cultivate something lush and vibrant.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • ADHD • learning disabilities • special education

Friday, February 03, 2006

Wrenches, Squeaky Wheels, and Autistic Families

This morning as I put Sweet M on the school bus at 7:15 it was actually starting to be light outside, even through the torrential rain. It is satisfying to see how the days are lengthening on each end, but particularly so in the morning, when we're usually still so bleary-eyed.

This morning as I put Sweet M on the school bus at 7:15 it was actually starting to be light outside, even through the torrential rain. It is satisfying to see how the days are lengthening on each end, but particularly so in the morning, when we're usually still so bleary-eyed.That's why it was especially bad news that M's bus driver Molly delivered: "The route has been changed, and starting Monday M's pickup time will be 6:30."

6:30? M's going to get on a bus at 6:30 in the morning to travel a distance of less than two and a half miles? She's going to sit on a bus for 90 minutes before she even starts her school day?

Cars were lining up behind the bus as I tried to get more information from Molly: Why the change? Who do I call? What's behind this? The waiting cars behind the flashing lights of the bus were patient enough, but if I'd blocked the street much longer they'd have been driven to honking, so I reluctantly released Molly and the bus to continue on their way—and I headed upstairs to call the OPT, the Office of Pupil Transportation.

The first operator I spoke with was no help at all, and insisted that there had been no change to the route or schedule. In fact, she kept trying to convince me that M has been being picked up at 6:30 since September, which might have been amusing if I wasn't so upset about this.

Right now we have finely tuned schedule. I get up at 6:30. Make M's breakfast and pack her lunch. Wake her up at 6:45, get her breakfast, teeth brushed, clothes on, and out the door, to be downstairs in time for the 7:10-7:20 pickup. I let her sleep to the absolute last minute because, like so many kids on or near the spectrum, she has a very difficult time getting to sleep at night. Always has. If she gets to sleep by 10:30–which is fairly typical for her—she's getting a little more than 8 hours of sleep on a good night, and that has been working for her.

Now, if she's supposed to be on the bus on at 6:30, I'll be getting her up at 6. Forty-five minutes earlier, 45 minutes less of deep, restorative REM sleep.

As most of you know, M has been doing pretty well at school this year. Her chronic meltdowns from last year have mostly stopped, and she's learning to read, to do double-column addition, and to play with her peers. Forty-five minutes less sleep could be a serious wrench in the works of this progress.

But operator #1 continued to insist that there had been no change—that M has been the first pickup on the route since September—until I said, "Okay, so let me just repeat what you're telling me because I'll probably have to call our education attorney to sort this out, and I want to make sure that I understand what you're saying."

"Oh," she said, "Oh yes, I see now that she used to be 6th on the route, and she was just changed to the first pickup. Well, there's nothing I can do about that."

"Okay," I said, "So at least we agree on the facts. Thanks, and have a great day."

I hung up, and called back and got a different operator, who was infinitely more helpful. She told me what was up: the school day has been lengthened by 37 minutes for kids in the general education population who need remediation, so they've completely changed all the bus schedules. She told me that I'd have to call the CSE, the Committee on Special Education, and she gave me the name of the person to call and a phone number.

The CSE doesn't open until 8:00, so I waited until then to call. At 8:20 I was still getting the recorded message saying that they open at 8. I have to admit that it seemed more than a little ironic that they expect little kids to get up at 6 a.m. to spend 90 minutes traveling 2.5 miles to school when they can't even get their own offices opened by eight.

The number I was calling was a general number, so I figured I'd better get this CSE official's direct line. This is the moment where we pause and say thank god for the internet. Ten seconds later I had his direct number. A woman answered the phone, and transferred me to someone's voicemail—but not to the voicemail of the CSE official I was calling. So I hung up, and called back, and miraculously got the head of the CSE for my district on the phone. He answered his own phone.

While I was sorely tempted to launch into my screed about how they don't answer their main phone line and have some kind of nerve to have kids riding buses for 90 minutes, this was definitely not the time for that. This was the time for honey-voice.

Honey-voice was born when I was sixteen years old and working at a movie theatre box office, answering the telephone and selling tickets. Long before the days of voicemail recorded schedules for movie times, teenagers like me answered the phone and told people what time the shows started and what the tickets cost. It sounds easy, but actually, it was fairly annoying as jobs go. The reality is that many people are cranky and irritable on the phone with people that they never expect to meet. In fact, they can be downright abusive. Enter honey-voice.

Honey-voice has a sickeningly sweet, deliciously seductive cadence: "Monica Twin Theatres, how can I help you?" I'd murmur into the phone, as if offering any pleasure imaginable rather than tickets to the usually G or PG-rated films.

It was remarkable. While my box office coworker continued to get nasty calls, my rude callers dropped to almost zero. I even had callers ring back, just to "double check the show times and say hi." And this was in the days before phone sex.

When people came to the box office to actually buy their tickets they had no idea that this honey-voiced theatre employee was me because when I was selling tickets I'd just use my regular voice.

Honey-voice, or a rather less suggestive, more maternal version of her, served me well this morning. I explained the problem with the change and how we had worked so hard this year to get M's behavioral issues under control so that she wouldn't have to be placed in a more restrictive, more costly setting, and that we didn't want to throw a wrench in the works by having her be exhausted every day at school.

The CSE official said he'd handle it right away—walk it over to the desk of the person in charge of my child's case immediately. And, amazingly, within 15 minutes I had a return phone call.

You would have to have had other experiences with the New York City Department of Education to know just how exceedingly unusual this is. I guess that in spite of my honey voice, they could tell that I am at heart a squeaky wheel, at least when it comes to getting Sweet M what she needs. Just like me, mindful this morning that the cars waiting behind the bus would eventually start honking, they decided to keep the wheels turning.

The woman who called back even opened the phone call with a joke: "I hear the Department of Education has offered to provide your child with a scenic tour of Manhattan every morning." She told me that I'd have to ask Sweet M's doctor to provide a note stating that for medical reasons she needs "limited time travel of no more than 60 minutes." Then I'd have to fax this to the a particular person at the DOE, and ask for an expedited hearing.

So it sounds as if even though I'll get the doctor's note today, that we'll be putting Sweet M on a bus at 6:30 am for at least a week or so, because an expedited decision could be a month or more from now. And I haven't even begun to figure out how we'll work out the afternoon piece of this: if she gets home at 4:30, how will she be able to make it to her 4:00 afterschool speech therapy two days a week? I am reminded of Kristina Chew, who had to move heaven and earth, and race the Pulaski Skyway, to cover 15 minutes in Charlie's afternoon.

And then there is the problem of changing buses: if we make a fuss about all of this—and get get limited time travel—she could find herself scheduled on a different route, with a different bus driver and different bus matron. We've had this team for two years, and they know M really well, so we'd really prefer to stick with the same people.

And, in all of this, I found myself wondering about something. Last week I went to a conference developed by Valerie Paradiz and the ASPIE School, and hosted by Marymount Manhattan College, on creating schools for aspie teens. One of the presenters talked about "autistic families"—not as families made up completely of autism spectrum individuals, but families where one person's autism shaped the entire family's behavior, rendering the family rigid, inflexible, and unwilling to change routines.

I wondered if I've become an autistic mom: Am I being rigid and inflexible, or is it outrageous to ask a kid to ride a bus for 90 minutes to travel a distance of 2.5 miles?

Bus matron Launa, Sweet M, and, concealed behind the wheel, reliable driver Molly.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • parenting • special education • education

Thursday, February 02, 2006

The Band-aid Fetish

In keeping with this week's inadvertent themes of aches, mourning, and sources of nurturance, Sweet M resumed her band-aid fixation.

Most of Sweet M's obsessions have receded in the past three years. We no longer have to stop at every payphone to dial pretend phone calls, or be sure she gets to swipe the credit card at the supermarket checkout counter, or make sure that no one else in an elevator pushes any of the number buttons. But, to my surprise, her band-aid fetish remains.

For a while I was using my reverse psychology approach—going all out on band-aids, making sure we had nearly every cartoon character: Barbie and Care Bears, Scoopy-Doo and Dora, Strawberry Shortcake and Sponge Bob.

Eventually, I figured, she'd just get tired of band-aids.

Wrong.

Retrospectively I can see the madness of this: why would she ever tire of them when they were so much fun? But, at the time, indulgence was my strategy.

On any given day we'd have at least 4 or 5 choices of band-aids around, and she'd have several on her fingers. They were sort of a disposable jewelry or body art. She seemed to like to fidget with them in class. At one point, I'd say we were spending about 20 dollars a month on band-aids. Sometimes, if we weren't careful, she'd leave one on for too long and the skin on her finger would get irritated, rubbed raw from the adhesive or the water that collected under the bandage.

Since my reverse psychology wasn't working, we slowly weaned her from the many colored and many charactered collection of band-aids. We kept the band-aid boxes out of sight, and only allowed them for actual bonafide injuries.

Last week M had a little paper cut. Her father had gotten a giant economy size box of regular beige-y camoflage "sheer" band-aids, and so we pulled it out and dressed the tiny cut. And left the band-aid box on the kitchen shelf.

Last week M had a little paper cut. Her father had gotten a giant economy size box of regular beige-y camoflage "sheer" band-aids, and so we pulled it out and dressed the tiny cut. And left the band-aid box on the kitchen shelf.Mistake.

Last night after M's bath she was changing her own band-aid, and F noticed that she'd wrapped a band-aid around her finger so tightly that she was cutting off the circulation. Then I noticed that she was actually changing the band-aids on not one, but four fingers. I don't know how long she'd been wrapping these fingers—probably for at least a week. I hadn't noticed the flesh-toned bandaids, designed as they are, to blend in, and her skin was irritated and peeling under the supposedly comforting and inconspicuous wraps.

We carefully pulled off the band-aids and dressed the distressed skin with an ointment, then wrapped up her little fingers in a gauzy wrap that would let the air get to her skin. Sort of an uber-bandage.

What strikes me about Sweet M is how what she does isn't all that different than what any of us do: the way she'd chosen to comfort herself, to care for herself, had become an unexpected self-injurious behavior.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)