In a book called Weaving a Family: Untangling Race and Adoption, the sociologist Barbara Katz Rothman has written movingly about her experience of parenting an adopted daughter who is African American, when Rothman is herself ethnically Jewish and racially white.

In a book called Weaving a Family: Untangling Race and Adoption, the sociologist Barbara Katz Rothman has written movingly about her experience of parenting an adopted daughter who is African American, when Rothman is herself ethnically Jewish and racially white.She describes the social interactions in which she and her daughter Victoria have to announce and "perform" their relationship of mother and daughter because our racial stereotypes prevent us from seeing them as such. The guy at the ice cream truck assumes that they aren't together. The teacher at the school doesn't initially think of them as related. Rothman takes pains to head off these painful misrecognitions at the pass. She writes:

. . . I learned to stand behind her with my hand clearly on her shoulder when we rang the violin teacher's door. "Hello, I'm Barbara and this is my daughter Victoria," I say before the teacher can so much as open her mouth. And put her foot in it. I call Victoria "my daughter" like a newlywed on a fifties sitcom said "my husband." Often. With a big smile. Straight at you.

The fact of Rothman and her daughter's relationship is not an obvious social fact: they have to work to cut across racial stereotyping to announce themselves as a family, to gain our recognition of their relationship.

For those of us who are parenting kids on or near the autism spectrum, we often have exactly the opposite problem: we may look completely "normal." So normal, in fact, that the only possible explanation for our kids' outbursts or behavioral episodes—or whatever we decide to call these meltdown events—is bad parenting and bratty behavior.

While Rothman and Victoria have to "perform family" to be accepted as family, those of us parenting on or near the spectrum have to announce ourselves as not normal, as not-NT, in order to make ourselves and our children make sense in the world. Kristina Chew writes movingly of affixing the autism awareness magnet to the side of her car. I've only recently started announcing M's neurological predisposition when faced with either social hiccups or social catastrophes.

Being "out about being aut," in Chew's memorable phrase, becomes one of the questions that faces autism parents. It is not only a practical question of what to say to judgemental strangers in the midst of a child's crises des nerfs or to what extent a particular diagnosis will limit, or enhance, a child's educational opportunities. It's also a political question of to what extent one wants to eliminate one's own, or one's child's, neurological distinctiveness–to what extent one wants one's child to be able to cover or pass as NT.

For some, the goal of early intervention is to render the autistic child indistinguishable from his or her peers. The "triumphs over autism" described by autism moms such as Catherine Maurice or Patricia Stacey have as their evidence of success the indistinguishability of their children from their neurotypical peers. Participation in a general education classroom becomes the sign of hard won "victories" over autism. For others, the goal of autism education is to create a context in which autistic individuals can thrive, and to render the wider world more accepting and nurturant of neurological diversity. These issues of visibility and invisibility influence how we picture or represent autism.

Add to these issues the stereotype about kids in the spectrum: that they can be, and often are, unusually attractive. They are said to have an otherworldly beauty, to be nearly elfish in their enchanting loveliness. Autism expert Uta Frith writes: "Those familiar with images of children who suffer with other serious developmental disorders know that these children look handicapped. In contrast, more often than not, the child with autism strikes the observer with a haunting and somehow otherworldly beauty."

In the first pages of Clara Claiborne Park's remarkable 1967 memoir of her family's life with her autistic daughter (Elly in the memoir, but Jessy in life) she describes Jessy's changeling beauty. Kristina Chew writes of the cuteness factor that helps cut Charlie slack. Similarly I noticed early on that that M's public episodes, however disconcerting to those around her, were met with more grace when she was otherwise adorable.

The first time I became aware of the autism-otherworldly beauty construct was when I was still hoping that we'd find be able to find a pro bono attorney or advocate to handle our case against the New York City Board of Education. When I spoke with a possible attorney on the phone she remarked, "I can almost picture your daughter . . . She's probably extraordinarily beautiful, isn't she?"

At the time, she happened to be at her most beautiful . . . Disarmingly beautiful . . . I couldn't deny it.

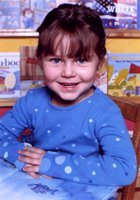

And, in fact, I think that her dazzling nursery school class picture may have contributed to some of the educational opportunities that she has enjoyed.

And, in fact, I think that her dazzling nursery school class picture may have contributed to some of the educational opportunities that she has enjoyed.Autism has its own beauty, its own aesthetic, but picturing autism isn't easy.

Keywords: autism • Asperger's Syndrome • parenting • Rothman, Barbara Katz • Maurice, Catherine • Stacey, Patricia • Park, Clara Claiborne

6 comments:

Where were you at the Autism and Representation conference in Cleveland in October 2005, my dear friend Mothers Vox--we could have used your perspective on this very topic! Though Park's work is not as well read as it ought to be, I think often of her use of the changeling metaphor. That peaceful look I have been describing in Charlie's eyes is indeed "otherworldly."

I suppose it could be said, Charlie has never appeared normal--too cute, too beautiful, too handsome, way before any word of autism.

On the other side, "normality" has never been part of the MO in our little family. My husband is ADHD and has spent his entire life down to today being "different" and having others inform him of this. I often think my understanding of Charlie's difference is rooted in my own experiences as an Asian/Chinese American. (When we lived in St. Louis, we were stared at because of the combo of Jim and me, excluded.) (Yes, unbelievable in this day and age---Minnesota was much more friendly to out "interracial" family.)

While a thorough ABA autism mother, I take issue with "Catherine Maurice" on multiple points. The goal of ABA ought not to be "indistinguishibility" but just giving a child the tools to learn and grow and be the best he or she can be. Charlie has never done so well as when we have tread that fine line between acceptance and instigation: This boy can go so far, no one can picture it.

I meant, "When we lived in St. Louis, we were stared at because of the combo of Jim [Irish Catholic] and me, exclusive of our neurologically diverse child.

Yes, the world needs to become more aware of autism spectrum differences. However, I'm concerned about the potential for emotional harm to a child when the parents regularly explain public misbehavior by saying that the child is autistic. A child who overhears such conversations could easily get the idea that being autistic equals being bad. Also, when parents mention autism as an explanation for misbehavior without discussing autism in other contexts, they are showing society only the negative side of autism.

When I was a child, I had some behavioral issues (getting hyper and running around in public places). As far as I know, my parents never felt that they were under any obligation to give psychological explanations for my behavior to judgmental strangers. They just took me home, gave me an explanation of what was wrong with my behavior, and sent me to my room for a while to think it over!

On the beauty stereotype: The autistic activist website Getting the Truth Out shows images of a woman who is not beautiful (she has scars from self-injury, keeps her hair cut short so that she won't pull it out, and sits in awkward positions). The first few pages describe how society sees her, and then she goes on to discuss how she sees the world and what she thinks of society's prejudices. That site does a brilliant job of smashing stereotypes.

There may be genetic reasons for why SOME autistic people are more attractive. (for one thing, an attractive autistic is more likely to reproduce than an unattractive one, it's like 2 hits: unattractiveness PUS autism are toooo much going against mate selection, though money helps-think: Bill Gates)

First of all, to most people on earth, wide-set eyes are more attractve than close-set eyes.

That is the farther eyes are from each other the better. This is a trait that is linked to very, very early embryological development. The positions that eyes take happens at about 20 days post conception which is the same time some of the proto neurology is being laid down.

At any rate, wide set eyes are one of the things I look for in doing my amateur autie-spotting.

There are other things that are genetically linked to autism that are not so attractive. You can see them in some kids who are held up as examples of those who are mercury poisoned from childhood vaccines. One thing, besides a large head that can't be linked to mercury or vaccines, is "malar hypoplasia". This is a sort of flattening of the cheekbones. Also, ASD kids MAY tend to have dark circles under their eyes because there is less nerve power (innervation?) going to the muscles right below the eyes (cheek muscles) the muscles sag and stretch the skin under the eyes.

Some autistic kids have a sort of soft look to their lower faces because they don't (can't) use their face muscles very well. I think it might contribute to a sort of "otherworldy" look, these are kids that look more "content" or something.

Besides the woman on "getting the truth out.org" who is basically certainly non-standard in her beauty, you can see a few hundred autistic adults on the a2p2, at www.isn.net/~jypsy/auspin/a2p2.html

It's hard to say but as a group, I'd say they were no more attractive or unattractive than NTs. But the more unattractive ones might be less willing to send in their photos... or maybe the more attractive ones are more likely to send in their photos...

One more thing, ASD women tend not to fuss over their appearance so you can imagine that some of us would look more "attractive" if we worked on our hair and makeup and clothese like typical women AND ASD folks seem to, on average be more thin or more fat than typical people, like we tend to go one way or the other. We have food issues so some don't eat much and we have depression issues so some of us may eat to assuage the depression.

Sweet M is a gorgeous child, though, no doubt.

My ASD child has a very unusual appearance, not pretty in some ways but stunning in other ways. I don't think that there are many people who have eyes that are more beautiful than my ASD kid's. My NT kid is pretty nice looking, too, and especially as a child was, at times, stunningly attractive.

Their father was kind of odd looking (there's something in the way of defective genes you can see), no body fat, and had/has gorgeous eyes, skin and hair.

Jessy Park is not that attractive looking now, but she may have been as a child.

My middle grandson is autistic and yes he is a gorgeous child. I believe that is due to the fact that there is such peace in his face, except for the times when he is in the middle of a melt-down and even then the pure frustration doesn't seem to reach his eyes. His eyes remain pure and untouched. He's five now, so we will have to see as the years go by, but I'm not sure if anything will ever change that look of calm in his eyes.

As to meltdowns, the child is the king. Normally, I let it be, but I have spoken out to people a few times, when the comments regarding my daughter's parenting skills have been loud and rude enough to bring her to tears. After all, she is still my baby, and after all, he is one of my grands. I suppose you could say I am one of those fiercely overprotective beasts of my own!!

Should be noted that many of us who may have fit the "unusually attractive" description as young children may not for many reasons continue to fit that description as adults.

Not that I understand a lot about what most people view as attractiveness. I find distinctiveness of appearance attractive, which means that many (but not all) of the people I view as aesthetically beautiful end up being people that others consider aesthetically ugly.

A friend told me last night that by my own standards I am probably attractive because I have a distinctly non-standard appearance, and by other people's standards I'd probably be midrange if I spent the amount of effort on my physical appearance that most women do. (I barely spend any effort on my physical appearance at all.)

I'd been told most of my adolescent to adult life that I was quite ugly and had people point out exactly why, but she said that what they were probably actually picking up on was behavior and hygiene. Then projecting a few non-standard aspects of my appearance (that would not be considered "ugly" perhaps, if I were neurotypical and more feminine-looking and better-groomed and and so forth) onto that already-there hygiene/behavior-based conception of me as ugly.

I certainly have the not-very-moving-much face and the large eyeballs though. (The eyeballs get compliments. Not much of the rest of me does.)

I find perception of attractiveness rather fascinating, not least because the standard version is so often far removed from my standards. I find autistic people unusually beautiful because we move in a distinctive set of patterns that stands out to me. I also find things like asymmetry, unusual body positions or configurations, and other things supposed to contribute to "ugliness," beautiful. So I really suspect the mechanisms for what I perceive as aesthetic beauty in people, and what other people perceive, must be totally different (there's some overlap but not a lot).

Needless to say, I suppose, I'm a Shrek fan. Although I always got called a troll (in the "ugly girl/mythical creature" sense, not the Internet sense), not an ogre.

Post a Comment