Santa descended upon us and much to M's delight, left only presents, and no lumps of coal.

Santa descended upon us and much to M's delight, left only presents, and no lumps of coal.But before we sprinkled the St. Nicholas dust and set out cookies and milk for the man in red, we went to a Christmas Eve celebration at the loft of some dear friends, Claire and Jerri. As the grown-ups gathered in the living room to talk and sing and nosh and drink and dance, Jerri set-up a DVD of Frosty the Snowman in their bedroom for M. and another little girl to watch. The other little girl soon joined the grown-ups to be with her mummy, but M. was happy amusing herself in their bedroom.

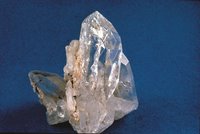

I wandered into the kitchen with Jerri to get some snacks, and peeked in on M., who was, to my amazement sitting in the center of the bed, cross-legged, and hands in a prayer position, obviously meditating. She'd placed a large quartz crystal that Claire and Jerri had on their dresser onto of a small pillow in the middle of the bed. As we watched from the kitchen, she began doing prostrations in front of this quartz crystal.

We were stunned. Where did she learn this? What is this about? I'd be just about the last person on the planet to buy into the indigo children hypothesis, but I have to say, I couldn't believe my eyes. We don't do yoga meditation at home with M. around. We don't have any crystals and candles set on altars at home. And yet here she was, deeply engaged in some kind of sacred practice.

I've asked her about it twice since then and she says, with great resolve, "Mama, I don't want to talk about it."

When M. was about four years old we were at the local supermarket check out paying for our groceries, and she suddenly got all panicked, as though she'd forgotten something.

"Fwow-wer," she'd said, "Fwow-wer."

She was agitated, so I let her take the lead. "Fowwer fowwer," she said with great urgency.

She led me back to the entrance of the store, and plucked a daisy from a mixed bouquet.

"Fowwer for ston addy. Fowwer for ston addy."

We hurried back to the cashier, and I thought she was going to give the flower to the cashier.

I said, "Did you want to give that to the lady?"

"NOOOOOOO . . . For ston addy ston addy ston addy," she started to lose it.

"Okay, okay, for ston addy," I said, not having the slightest idea what she or I were saying.

When we walked back home with our bag of groceries, I wanted to turn onto Thompson Street and take the shortcut across the playground, but she was adamant that we continue along Houston Street.

"No no no." She was tugging at my arm, dragging me along Houston toward Sullivan.

We rounded the corner, and she insisted on crossing the street.

"Ston addy ston addy," she said.

And there was the stone lady, a stone statue of the Virgin Mary outside the rectory of the Church of St. Anthony that marks the top of the block.

"Ston addy ston addy," she said, as she presented her purloined daisy to the ston addy.

I was dazzled. I don't know what to do with this sort of reverence—how to honor her spirituality and foster her spirit?